Photo by the author (May 2016).

In the third week of August 1944, at about the time the insurrection in Paris was beginning, an unexpected dispatch in Morse code reached the London headquarters of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), the British organization that conducted espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance in Nazi-occupied Europe. Having been sent in English through previously unknown Warsaw underground radio transmitter, it described the heavy fighting and horror that had reigned over the Polish capital. The SOE realized very quickly that the man behind the dispatch was none other than John Ward, the RAF sergeant and former prisoner of war who successfully escaped the German captivity in 1941 and had been acting ever since as a Polish resistance member. By the end of the month, Ward’s reports were being widely distributed in the British and the Western press. It was only then that the western public developed an awareness of Warsaw’s terrible fate.

A ‘Transnational Gorilla’ in the Uprising’s ‘Historiography Room’

The Warsaw Uprising against the German occupation lasted 63 days, from August 1 until October 2, 1944, resulting in the complete defeat of the resisters and the deaths of 200,000 civilians, has been traditionally almost completely ignored by the Western historiography of WWII. Therefore, the highly controversial The Warsaw Rising of 1944 (1974) by Jan Ciechanowski¹ – the former Polish resister who became after WWII a British historian and the main Uprising’s criticizer – was for three long decades the only comprehensive Western academic publication on this subject and the main source for quotations.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, this historiographical gap has at least been partly filled by a series of Western and translated Polish scholarships, such as Der Warschauer Aufstand 1944 (2001) by Włodzimierz Borodziej,² Rising ’44 (2004) by Norman Davies,³ Eagle Unbowed (2013) by Halik Kochanski,4 and Hitler’s Europe Ablaze (2014) by Philip Cooke and Ben Shepherd.5 Having been based on newly opened relevant Polish and Western archival collections and numerous personal testimonies of the resisters, they deal broadly with the Polish anti-Nazi resistance, as well as with the Warsaw Uprising per se.

Yet, what remained an almost complete enigma, not only in the West but also in Poland itself, is the Uprising’s transnational dimension. The active participation of hundreds of foreigners (to be described soon), who desperately attempted to liberate the Polish capital from the Nazis, has never been the subject of a separate academic monograph, Polish or Western alike,6 and was acknowledged and very briefly described by the permanent exhibition and the official website of the state Warsaw Uprising Museum (www.1944.pl) only during the last decade.7 Alas, the official narrative of the Uprising that serves the Polish educational system is still lacking any mention of any foreign involvement.8

The matter that seems to be elaborated somewhat better is the SOE’s assistance to the Polish national underground since 1941 and during the Warsaw Uprising in particular. Nonetheless, in this case, too, the above mentioned Western and Polish authors and their colleagues, being satisfied by mostly anecdotal descriptions of the SOE activity, failed to provide a detailed picture and scrupulous scientific analysis based on the primary British and Polish sources.9

The Red-White International

Photo by the author (May 2016).

The exact number of the foreigners, ‘obcokrajowcy’ in Polish, who fought for Poland’s independence, is difficult to determine, taking into consideration the chaotic character of the Uprising that caused very irregular registration of the resisters. By now, it is estimated that they numbered several hundred and represented at least 15 countries – Slovakia, Hungary, Great Britain, Australia, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Greece, Italy, the United States of America, the Soviet Union, South Africa, Rumania and even Germany and Nigeria.10

These people – emigrants who had settled in Warsaw before the war, escapees from numerous POW, concentration and labor camps, and deserters from the German auxiliary forces – were absorbed in different fighting and supportive formations of the Polish underground called ‘Armija Krajova’ (‘The Home Army’) or AK. They wore the underground’s red-white armband (the colors of the Polish national flag) and adopted the Polish traditional independence fighters’ slogan ‘Za naszą i waszą wolność’ (‘For our freedom and yours’), that dates back to the 1831 anti-Russian uprising and has been widely used by the International Brigades in Spain. Some of the ‘obcokrajowcy’ showed outstanding bravery in fighting the enemy and were awarded the highest decorations of the AK and the Polish government in exile.

Neighbors-in-arms

The current Polish historiography of the Uprising claims that its most numerous foreign participants came from two neighboring Eastern European countries, Slovakia and Hungary. The Slovakian residents of Warsaw, mostly political emigrants, had initiated their first contacts with the AK at the very beginning of the German occupation. In late 1942, they had established the underground Slovakian National Committee (SNK) and its military arm, the ‘Slovakian platoon No. 535’, which was subordinated to the Warsaw’s AK command. Among its 57 fighters only 28 were Slovaks. The rest consisted of other Slavic nationalities (Czechs, Poles and Ukrainians), as well as of Caucasians (Georgians, Armenians and Azerbaijanis). The most numerous were the Georgians who either came to the Polish capital from Russia, following the Bolshevik revolution, or escaped the German camps after being captured as the Red Army soldiers. Eventually, a separate Georgian sub-unit was established under the command of a Soviet POW nicknamed ‘Russjanschvili’ (‘The son of Russia’ in Georgian).11

The commander of the SNK and the ‘Slovakian platoon’, lieutenant Mirosław Iringh (‘Stanko’) – son of a Slovakian father, a political emigrant from Hungary, and a Polish mother – dedicated his pre-war life to journalism and participated actively in defense of Warsaw, in September 1939. Later on, he acted as a distributer of the Polish and Slovak underground press. During the Uprising, Iringh and his men had taken part in the fiercest street battles. In addition, the young lieutenant meticulously photographed combat scenes as well as the everyday life of the resisters and civilian population. He managed to survive the Uprising’s suppression.

Alas, the Polish new Communist authorities did not prize his contribution as a brave combatant and reporter. Because of his rank within the AK hierarchy, he was constantly denied any significant job and supported his family by working as unofficial street photographer. His health deteriorated and he died of lung cancer in 1985. It was only after the downfall of Communism in Eastern Europe that Mirosław Iringh became an official hero in Poland and Slovakia and had one of Warsaw’s squares named after him.12

Source: The official website of the Warsaw Uprising Museum, Poland.

http://www.1944.pl/

The Hungarians who joined the Polish resisters, and whose exact number is still unknown, were the deserters from the Hungarian military units that had participated in the German crackdown effort. Their comrades who did not desert were mostly sympathetic to the Polish cause and thus tried to preserve neutrality. They deliberately avoided combat with the AK units and frequently helped the insurgents by supplying ordnance and provision.13

Western Assistance – Intentional and Accidental

The only combat support that Great Britain intentionally provided to fighting Warsaw was a group of up to 100 Polish soldiers who came to the country from France, following its defeat in June 1940, and who were eventually recruited and trained by the SOE as special operations paratroopers. Officially, they had been part of a larger military formation called in Polish ‘Cichociemni’ (‘Silent and unseen’). This was established in 1941, supervised by the Polish General Staff in exile, and performed guerrilla, sabotage and reconnaissance missions in Nazi-occupied Poland.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AKrasinski_Adam.jpg

Serving as either field commanders or rank and file fighters during the Warsaw Uprising, the ‘Cichociemni’ fighters made successful use of the knowledge and operational skills they gained from the SOE and taught their fellow combatants. Yet they had paid a heavy personal price for being the vanguard of the resistance: at least 18 of them were killed, and many more were wounded, reported as missing in action or captured by the Germans, and imprisoned and executed.14

The survivors suffered from the Communists’ persecution, and only a handful of them managed to return to England. Their bravery has been obscured for many years in Poland and England alike, and was finally ‘discovered’ and prized in a few Polish and English books and documentary films in the past three decades.15 Nevertheless, their story has not yet been adopted by the SOE ‘mainstream narrative’, and, therefore, the most updated biography of the organization’s chief, Major-General Colin Gubbins – SOE’s Mastermind (2016) by Brian Lett – did not mention the Warsaw Uprising and claimed only that the Polish Home Army was quite effective, but the Britons had no real possibility of supporting it.16

Besides the Poles, who willingly returned from the West in order to restore their motherland’s independence, there were also other uncounted Westerners – mostly escapees form the German POW camps – who found themselves more or less intentionally in the eye of the Uprising’s storm. Probably, the most famous is the story of John Ward, the young RAF sergeant from Birmingham. In May 1940, aged only 21, he was shot down and captured by the Germans in France, sent to a labor camp in Poland, almost immediately escaped, was recaptured, escaped again, and finally found his way to the AK underground. By the outbreak of the Uprising, in August 1944, he had already spent about two long years in the Polish capital, training Polish radio operators, transcribing BBC broadcasts for the underground press, producing his own illegal newspaper and serving simultaneously as a liaison between the AK and the British authorities and a field reporter for the London Times.

Source: http://polishgreatness.blogspot.co.uk/2011/09/warsaw-uprising-1944-september-12-lt.html

During the 63 days of the Uprising, Ward transmitted to the SOE and the British press numerous reports on the combat and humanitarian situation in the Polish capital. Simultaneously, he served as an English-speaking announcer for the underground radio station ‘Błyskawica’ (‘Lightening’). It was to a substantial degree thanks to him that the Western public and the policymakers became aware of the Uprising and its terrible outcome. When the resistance was over, he was captured while posing as a Pole, escaped to the Polish partisans, arrested as a ‘spy’ by the Soviet secret service NKVD, rescued by an American representative and finally left for England via the Soviet Union among a group of former American and British POWs. In the early 1990s, the AK English radio announcer was still alive to witness the downfall of Communism in his beloved Poland. The new Polish government awarded him two high military decorations as recognition of his bravery and contribution to the struggle against the Nazis.17

Another amazing destiny was that of Walter E. Smith, a signalman of the Australian Expeditionary Force who had been taken prisoner on Crete, in May 1941, sent like John Ward to a POW camp in Poland and managed to escape – at his seventh attempt (!) – using false documents supplied by the local underground. Despite not being involved in active fighting, he nonetheless contributed to the AK propaganda effort by broadcasting their interview with him, which was reported by the Australian press and re-distributed worldwide. Smith too was able to return to his homeland following the German retreat from Poland.18

There are also several testimonies of the Uprising’s veterans concerning the presence of at least five French comrades among the resisters. Only one of them, Jean Gasparoux, is known by name. Aged about 26, he allegedly spent all the occupation years in Warsaw and, following the Uprising’s breakout, joined the AK ‘Bałtyk’ platoon as a sniper. He was subsequently captured by the Germans and acknowledged by his comrades at a POW prison, but his later fate is unknown.19

The Russian ‘Ghosts’

The current official Polish Uprising’s historiography has its ‘black hole’ that relates to the contribution of the Soviet prisoners of war. Although their exact number has yet to be established, different estimations speak of up to 60 persons. Among them, 20 Soviet officers, allegedly from the NKVD border guard, who had been released by the AK from one of the German prisons, volunteered to join the resisters and consequently died in heavy street fighting. No names are known, except that of lieutenant Viktor Bashmakov (‘Engineer’), aged 28, who served as a commander of the separate Russian AK platoon and was killed, along with his soldiers on 30 September 1944.20

Source: Russian historical website ‘Petr i mazepA’.

http://petrimazepa.com/warsaw.html

In addition, there were a few Russian escapees from the Warsaw concentration camp, as well as deserters from the Wehrmacht’s collaborationist forces (Russians and Caucasians alike) that consisted of former Soviet prisoners of war, who had been assigned to anti-partisan missions in the Polish capital. These people randomly joined different AK units, and most of them died in battles in complete anonymity.21

From Crematorium to Burning Streets

On 5 August 1944, during the initial phase of the Warsaw Uprising, a battalion of the AK ‘Radosław’ group attacked the ‘Gęsiówka’ concentration camp – a facility in the city center, equipped with a crematorium and populated by slave laborers, mostly Jews form the liquidated Warsaw Ghetto and different European countries. At least 50 of the 348 released Jewish prisoners, males and females, including citizens of Germany, Holland, Greece and Hungary, joined their liberators, mostly as supportive manpower that transported injured fighters, produced arms and munition, fought fires, etc. Most of these people died during the heavy fighting on Warsaw streets or were captured and executed by the Nazis.22

Source: The official website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Juliusz Bogdan Deczkowski. https://www.ushmm.org/search/results/?q=98679

Nigeria-on-Vistula

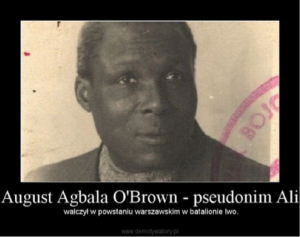

During the 1990s, while sharing with historians and journalists their memories about the Warsaw Uprising, some of the still living former Polish resisters recalled that there had been among them an African comrade who had fought bravely. Initially, this claim was dismissed as nonsense, but subsequently discovered archival information and additional testimonies proved its reliability.

His name was August Agbala O’Brown (sometimes referred to as Browne). He was born in Lagos, the largest city of modern-day Nigeria, in 1895. Since there is no information whatsoever about his early life and career, his curriculum vitae starts in 1922, when after stowing away on a sea ship he travelled to Poland via England and the ‘free town’ Danzig (later Polish Gdansk). A short period of hard physical work in the polish docks came to an end when he started to perform as a jazz drummer in the leading Warsaw night clubs and shortly afterwards became a celebrity of the local musical scene. His first album, recorded in 1928, made history, for he was the first West-African jazzman to achieve this. The process of integration into Polish society culminated in O’Brown’s marriage to a Polish girl, who gave birth to two boys. His friends and neighbors at the time remembered him as a very intelligent, courteous person, and a polyglot (he spoke six languages!).

Source: http://staraprasa.blox.pl/2012/08/Czarny-powstaniec-August-Browne.html

Source: http://staraprasa.blox.pl/2012/08/Czarny-powstaniec-August-Browne.html

Yet O’Brown’s life was to change drastically in the autumn of 1939. In the face of the Wehrmacht’s rapid advance toward Warsaw, the majority of the tiny local African community – mostly musicians from different Western countries – flew abroad, but the Nigerian jazzman decided to stay with his new Polish family and friends. In the weeks that followed, he participated in the defense of the Polish capital, and after its surrender went underground adopting the alias ‘Ali’. Despite the danger of being caught, because of his obviously ‘non-Aryan’ appearance, he was, on a number of occasions, seen around Warsaw, distributing the AK news-sheet.

Source: The official website of the Warsaw Uprising Museum, Poland.

http://www.1944.pl/historia/powstancze-biogramy/August_OBrown

Amazingly, O’Brown succeeded in surviving the next five years of German occupation and actively participated in the Warsaw Uprising, as a common fighter of the AK battalion ‘Iwo’. He had not been injured and had successfully escaped possible German captivity. He soon witnessed the Soviet conquest of the country and the imposing of the Communist regime. The new rulers showed patience by awarding ‘the African comrade’ for his struggle against the Nazis, allowing him to play jazz at Warsaw restaurants and even hiring him as a ‘cultural officer’ for a governmental institution.

Source: The official website of the Warsaw Uprising Museum, Poland.

http://www.1944.pl/historia/powstancze-biogramy/August_OBrown

In the mid-1950s, the pioneer of West African jazz and the only African fighter of the Polish underground, August Agbala O’Brown, might still be seen playing music at various Warsaw’s stages. However, by the end of the decade, already aged over 60, he became completely frustrated with the ‘Communist heaven’ and got special permission from the authorities to take his family to England. There he lived anonymously for almost two additional decades and passed away in 1976.23

Conclusions

Although several hundred foreign fighters made up barely one percent of the total number of Warsaw resisters, their presence converted the Uprising into a unique event in comparison with other, more ‘nationally homogenous’, anti-Nazi and anti-Soviet rebellions in Poland itself and in other countries, except perhaps the almost simultaneous Paris Uprising. Interestingly, it was a continuation of a phenomenon that characterized two Polish anti-Russian mutinies in the 19th century. The latter, which broke out in 1863, attracted up to 1,000 foreign volunteers.24

There is already sufficient existing knowledge concerning the personal backgrounds of the foreigners who joined the Warsaw Uprising, to allow us to present five different types of routes that brought them to the fighting Polish capital:

• Western and Soviet POWs (sometimes captured at very distant theaters of war, like the Mediterranean) who escaped prior to or had been released during the Uprising;

• Deserters from the German auxiliary forces (former Soviet POWs and Hungarians);

• Inmates of the Warsaw concentration camp (mostly foreign Jews);

• Paratroopers sent by the British SOE from England (Poles who had escaped their homeland in Autumn 1939);

• Emigrants (either political or economic) who were living in Poland and its capital before WWII (Slovaks, Georgians, and a Nigerian).

In contrast, our knowledge about the ‘transnationalizing processes’ in the virtual space that embraces the local Polish resisters and their foreign comrades still suffers from many gaps. It is known that there had been a transfer of martial and technical knowledge and skills from the trained and experienced strangers to their hosts, as well as mutual operational activity, but the specific patterns and mechanisms of this amalgamation have yet to be discovered and thoroughly investigated. Unfortunately, the existing Western and Polish secondary sources are of almost no value for this mission, since they have not been resolute in highlighting the transnational dimension of the Warsaw Uprising and contain only sporadic anecdotal descriptions of its expressions. Thus, forthcoming research should concentrate on scrupulous work with relevant primary archival sources and recorded veterans’ testimonies.

Notes

1Jan Ciechanowski, The Warsaw Rising of 1944 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1974).

2Włodzimierz Borodziej, Der Warschauer Aufstand 1944 [The Warsaw Uprising of 1944] (S. Fischer Verlag: Frankfurt am Main, 2001).

3Norman Davies, Rising ’44. ‘Battle for Warsaw’ (Pan Macmillan: London, 2004).

4Halik Kochanski, Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the poles in the Second World War (Penguin Books: London, 2013).

5Philip Cooke and Ben Shepherd, Hitler’s Europe Ablaze: Occupation, Resistance and Rebellion During World War II (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2014).

6There has been a censored Communist-era book dedicated to this subject that can hardly be called ‘a scientific monograph’. See: Stanisław Okęcki, Cudzoziemcy w polskim ruchu oporu: 1939-1945 (Warszawa: Interpress, 1975).

7See: ‘Hołd dla Słowaków’ [‘Homage to Slovaks’], 10.06.2005, Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego. Retrieved from: http://www.1944.pl/o_muzeum/news/hold_dla_slowakow/?q=iringh. Last visited: 13.07.2016; ‘Obcokrajowcy w Powstaniu’ [‘Foreigners in the Uprising’], No date, Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego. Retrieved from: http://www.1944.pl/o_muzeum/ekspozycja/1_pietro/39_obcokrajowcy_w_powstaniu/?q=iringh. Last visited: 13.07.2016.

See also the insufficient historical attention paid to the Uprising’s foreign participants in the interview with Katarzyna Utracka, a historian at the Warsaw Uprising Museum: ‘Nieodkryta karta’ [‘Undiscovered card’], Polska Zbrojna, 14.08.2012. Retrieved from: http://www.polska-zbrojna.pl/home/articleinmagazineshow/4732?t=ZA-WOLNOSC-WASZA. Last visited: 14.07.2016.

8See for example: R. Dolecki, J. Smoleński and K. Gutowski, Po prostu Histotia. Podręcznik, Szkoły ponadgimnazjalne [Simple History. Textbook for high schools] (Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne sp. z.o.o.: Warszawa, 2013), Chapter VIII, pp. 200-254.

9For example, Norman Davies’s book mentions only briefly, on four different occasions, the participation in the Uprising of a British sergeant John Ward and the SOE Polish paratroopers called ‘Cichociemni’ (to be described further). The footnotes testify that the information about the paratroopers has been retrieved from a book published in Communist Poland in 1985. See: Davies, op. cit., pp. 191, 288, 324-325, 464-466; the Kochanski’s book does not mention Ward or other foreigners and reminds the ‘Cichociemni’ only sporadically. See: Kochanski, op. cit., pp. 228, 286, 364.

10‘Obcokrajowcy w Powstaniu’, op. cit.

11Ibid.; Waldemar Ireneusz Oszczęda, ‘Udiał Słowaków w Powstaniu Warszawskim’, Almanach Muszyny 2008, pp. 87-92. Retrieved from: http://www.almanachmuszyny.pl/spisy/2008/UDZIAL%20SLOWAKOW.pdf. Last visited: 14.07.2016.

12Ibid.; “Mirosław Iringh”, No date, Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego. Retrieved from: http://www.1944.pl/historia/powstancze-biogramy/Miroslaw_Iringh. Last visited: 14.07.2016.

13‘Obcokrajowcy w Powstaniu’, op. cit.

14Davies, op. cit., p. 191; Kochanski, op. cit., pp. 228, 268, 364; Grzegorz Korcziński, Polskie oddziały specjalne w II wojnie światowej [Polish special forces in WWII] (Warszawa: Bellona, 2006), p. 60; Jan Szatsznaider, Cichiociemni. Z Polski do Polski [Cichociemni. From Poland to Poland] (Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza: Wrocław, 1985).

15Ibid.

16Brian Lett, SOE’s Mastermind. An Authorised Biography of Major General Sir Colin Gubbins Kcmg, DSO, MC (Barnsley, South Yorkshire, England: Pen & Sword Military, 2016).

17Davies, op. cit., pp. 268, 324-325, 464-466; Stefan Karbonski, Fighting Warsaw (London: George Allen & Unwin, Ltd., 1956), pp. 358-362; Johnathan Walker, Poland Alone: Britain, SOE, and the Collapse of the Polish Resistance 1944 (London: The History Press, 2011), pp. 40, 53, 76.

18‘Missing Men from 1945’, National Ex-prisoner of War Association, Autumn 2013 Newsletter, p. 9. Retrieved from: http://www.prisonerofwar.org.uk/AUTUMN%202013%20NEWSLETTER.pdf. Last visited: 14.07.2016.

19Piotr Wróblewski, ‘Waleczny Francuz na murach Warszawy. Znacie jego historię?’, Naszemiasto.pl, 23.06.2016. Retrieved from: http://warszawa.naszemiasto.pl/artykul/waleczny-francuz-na-murach-warszawy-znacie-jego-historie,3451335,artgal,t,id,tm.html. Last visited: 14.07.2016.

20Roman Vol’nodumov, ‘Russkie i varshavskoe vosstanie’ [‘The Russians and the Warsaw Uprising’], Russian historical website ‘Petr I mazepA’. Retrieved from: http://petrimazepa.com/warsaw.html. Last visited: 13.07.2016.

21Ibid.

22Kopka, Konzentrationslager Warschau: historia i następstwa (Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2007), pp. 101-112; ‘Obcokrajowcy w Powstaniu’, op. cit.; ‘Za wolność waszą ’, Polska Zbrojna, 14.08.2012. Retrieved from: http://www.polska-zbrojna.pl/home/articleinmagazineshow/4732?t=ZA-WOLNOSC-WASZA. Last visited: 14.07.2016.

23‘August Agbola O’Brown’, No date, Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego. Retrieved from: http://www.1944.pl/historia/powstancze-biogramy/August_OBrown. Last visited: 14.07.2016.

Ed Keazor, ‘August Agboola Browne Nigerian pioneer of Jazz music and World War 2 hero’, Music in Africa Magazine, 29.05.2015. Retrieved from: http://musicinafrica.net/august-agboola-browne-nigerian-pioneer-jazz-music-and-world-war-2-hero. Last visited: 14.07.2016.

24Dorota Truszczak i Andrzej Sowa, ‘Powstanie styczniowe: obcy też walczyli za naszą wolność’ [‘The January Uprising: Foreigners had fought for our freedom too’], Polskie Radio, 24.07.2013. Retrieved from: http://www.polskieradio.pl/7/2612/Artykul/895066,Powstanie-styczniowe-obcy-tez-walczyli-za-nasza-wolnosc. Last visited: 13.07.2016.